Dark Black Depths -

The Questions of Faith as Asked in Painting

by Frank-Thorsten Moll

“Art has to come over people like a cloud and, in the final analysis, a picture should keep alive a profound question in people. Art is, as such, a puzzle.”

Joseph Beuys, 1984

Rustling and billowing, the rays of the sun penetrate through scattered cloud and fog formations. It is as though a hazy twilight had settled down over Philipp Haager’s paintings, enveloping them in an enigmatic atmosphere. Every one of them offers the viewer with its mysterious darkness a gaze into sheerly endless depths. Meanwhile, the artist’s latest works from the past two years have ventured away from the dominance of black and gray and are increasingly beginning to glow – although here we must understand glowing neither as a “glaring blaze” nor as an “aggressive signaling.” Even in Near Field Phase 3 (2009), the fleshy red is forbidden to break through with too much flamboyance, because Philipp Haager has reined in even this, his wildest work in terms of color, with a black-and-gray sfumato. Surely this is to ensure that the moment framed in the picture remains one of those indecisive moments of upheaval that have always characterized his paintings: moments of upheaval in which day has only just let night in through the back door to plunge the space little by little in darkness.

For years, Haager’s usually large-format paintings have been created in an almost loving process of accumulation of material, through patient application of India ink on canvas and the subtraction of matter, through systematic washing away of the ink with repeated sprays of water.[1] Long drying periods are always followed by renewed waterings – a rhythm that dictates the essence of the picture just as do light and shadow, condensing and breaking up.[2] His pictures glide on a current of constant change and are borne by the desire to arrive, even using the simplest of means – i.e. as an ink painter using “dirty water” – at a holistic-seeming view of an “existence.” Whether this is even possible within the medium of painting is the question at the heart of all his work, as he told me in an email.[3]

On my last visit to his studio, there was, as always, a row of unfinished pictures propped against the wall and, as always, they dripped silently but steadily into vessels placed below to catch the runoff – as if they were weeping or being bled like slaughtered animals hanging from the wall.[4] One quickly notices, though, that a conspicuous change has taken place – a new base tone has entered into his pictures, together with new colors, sometimes several at once. The pictures no longer hum in the heavy, earthy minor key of before, nor does their own visual weight drag them down as if they wanted to merge with the earth on which they’re standing. They look lighter and appear almost to float, as if the piled-up clouds depicted had decided to take the canvas and stretcher frame of which they’re made into their own hands in order to hoist themselves upward. It is surely no exaggeration to say that Haager’s pictures exude an almost disarming self-assurance. Everything seems possible in and with his latest paintings, for example the green-dipped Near Field Phase 4 (2009), or Near Field Phase 2 (2009), into whose gray-and-black references to the erstwhile pictorial severity is mixed a reddish undertone that corresponds perfectly with Near Field Phase 3 (2009).

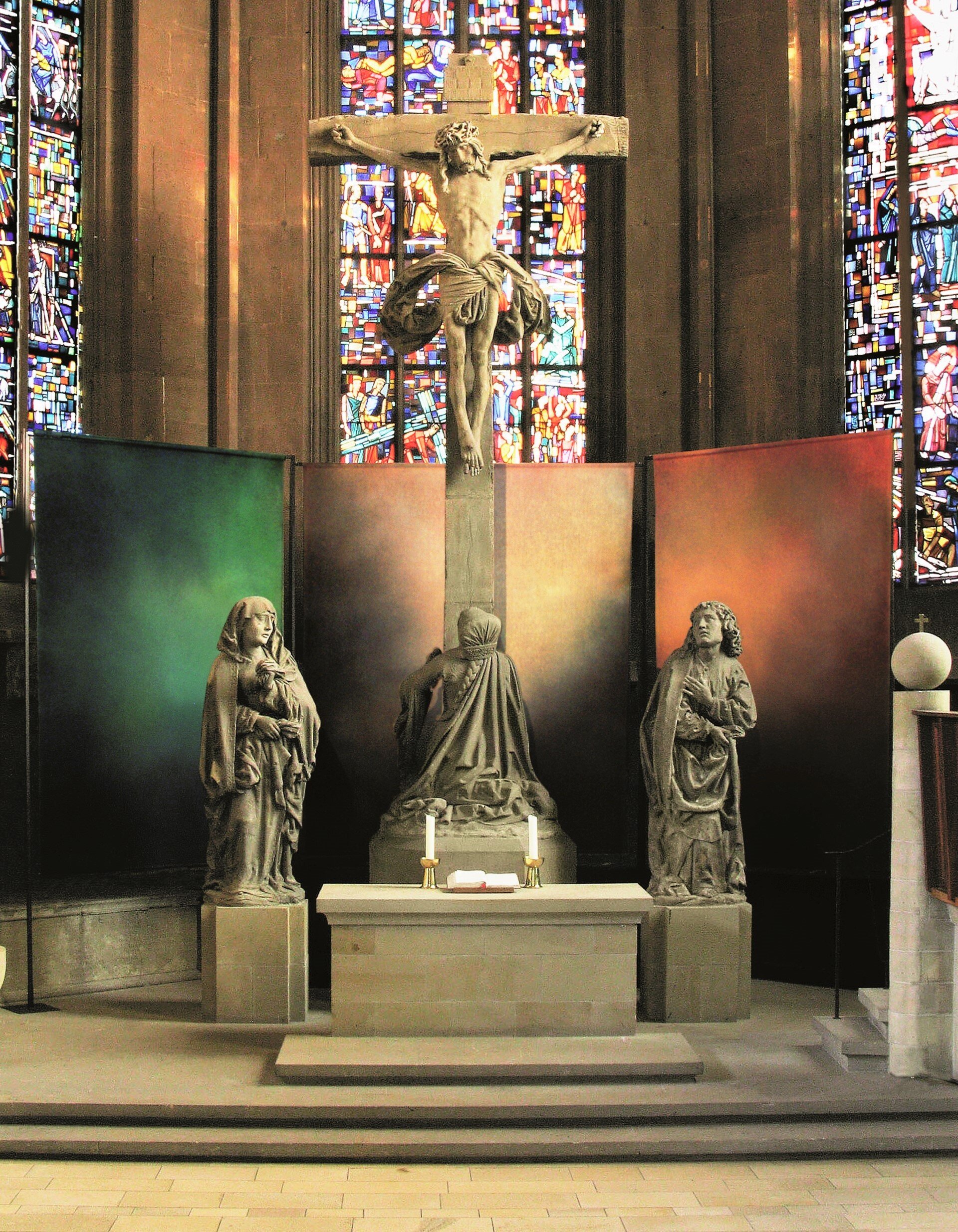

The new lightness these paintings radiate despite all their earnestness was put to the test when Philipp Haager bravely exhibited one of them as altar triptych in the exhibition “Phasis (Bilder dem Herrn)” at the Hospital Church in Stuttgart. Melting Memory (2010), as he named the installation, represents one of the few successful attempts at integrating painting into the existing church context and in the process detracting neither from the church space nor the paintings themselves. The pictures installed behind the figural group at the altar enter into a perfect symbiosis with their setting; they even immensely enhance the dramatic scene of Jesus Christ nailed to the Cross with the figures of Mary and John standing below. In this altered spatial context as well, the pictures veritably surge upward, almost as if they were to foretell Jesus’ ascension into heaven. Religion and art? Faith and pictorialism? Doesn’t this remind us of all those centuries during which artists acted within the clearly defined iconographic confines dictated by their clients, before they slowly extricated themselves from such relationships? Surely, the eternally virulent question of the autonomy of art must play an important role here, because Haager deliberately uses it to present himself self-confidently as a seeker and a questioner.

Since the transience of one’s own existence is the most difficult to bear of all the questions facing us mortals, Haager is convinced that painting must hold answers to this shattering fact, or that it must at least ask the question of what will one day remain of all that we humans have created. For Haager, painting has thus once again become a question of faith. What makes this interesting in the present context is that here a central question asked by many religions is being disengaged from their doctrines and is being converted into an artistic question; what’s more, the outcome of this conversion is being transported back into the realm of the church.[5] There is no doubt that examining the pictures in the Hospital Church elicits interesting overlaps on various levels of content and form. We might perhaps assume, for example, that the painted cloud landscapes at the altar are something like a conventional depiction of nature, were it not for their rootlessness, which prompts “atmospheric spatial uncertainty.”[6] As altar paintings, Haager’s pictures are always both – site-specific and rootless, since they adopt the most rootless genre there is: the cloud picture.

In Christian iconography the cloud is of course more than just a meteorological phenomenon. It symbolizes the presence of God and acts as mediator between Heaven and Earth. It is therefore no wonder that in innumerable pictures God is shown enthroned on a cloud, floating down to Earth, and that he conversely lifted Jesus Christ up to Heaven on a cloud.[7] For millennia, the cloud has been one of the most powerful pictorial instruments in a vertical spatial logic based on the heights of the divine space (up above) and the depths of the earthly space (here below). All aspects of a human existence that strives for something “higher” have since then taken place in the space between Heaven and Earth. The cloud is then a kind of “iconographic elevator” that takes us up to Heaven.

The Ancient Greeks were not the first or only culture to incorporate wind or storm gods in their myths. The Biblical God Yahweh is also a weather god, often appearing cloaked in weather elements, especially in clouds.[8] We can therefore read Haager’s intervention as a strategy for giving the Christian God back His weather garb or, more precisely, his mantle of clouds, by clothing the sculptural group in a painterly cloak of cloud pictures. Moreover, clouds and weather are also a daily source and reflection of our moods: “We read into them and out of them what we feel; our emotions fulminate and blow hot and cold just like the clouds and winds themselves.”[9]

Neither philosophical nor scientific enlightenment has yet been able to defuse this almost mystic charge. The elemental power of Haager’s painting pays tribute to this persistence, just as it does to the fact that cloud painting was only able to develop as a painting subject in its own right after artists had managed to free themselves from their Christian patrons, embarking on its own proud career as independent motif once painting had gained a more autonomous standing in the 18th and 19th centuries.[10]

The milestones of this singularly painterly development can be found in the work of Henri Pierre, Henri de Valenciennes, Alexander Gozens and Luke Howards – or in Johann Georg von Dillis, John Constable, Carl Blechen and William Turner. All of these painters associated cloud pictures with the liberation of the painting hand, “which could now apply in oil, in watercolor or in forcefully drawn, dynamic strokes, in keeping with the volatility of the phenomenon, the colors, contours and bulk of the cloud bodies – in outdoor sketches that were later executed in the studio and then exhibited to the astonishment of the public.”[11]

It would almost be too daring to assert that with this genre Haager is returning to the symbolic place from which modernist painting sought to emancipate itself; we can say instead that he is carrying forward the emancipation of the painting hand – by making his pictures into pouring and watering events.

But there is another aspect that lends his cloud pictures an atmosphere of transition. His paintings always look as though they were enveloped in a fine mist that both dissolves and unifies the subject. For Gernot Böhme, this haze even constitutes a kind of totalization[12] of the picture since it gives greater weight to the imagination and subjectivity of the viewer.[13] One can go still further and point out that things seem to emerge out of this mist, that they give the impression of being suspended therein. “They are in an emphatic sense manifestations,”[14] just like the sculptures in the church, which begin to glow and float in the misty atmosphere created by the pictures.

Haager unfolds in his painting an ambivalent twilight dynamic with an almost literary character, belying the assumption made by many that painting is unable to represent inner temporal structures in a kind of “flow of words” similar to a literary narrative.

He succeeds at this through the logic of the triptych, which has always been understood as a tool for narration, no matter of which sort, but also by dissolving the edges of the picture in a blurriness that, with the help of colors, makes them seem to extend into church space. He does away with the frame as the natural boundary of the picture and hence demonstrates a renewed aspiration to give painting back much of what it seems to have lost on the way to its own autonomy. We can see this above all in the confidence with which Haager’s painting asserts its own place within the church – a confidence that leaves no room for even the slightest doubt about the autonomy of art.

July 2010

[1] Frank-Thorsten Moll, Was übrig bleibt, wenn nichts mehr übrig bleibt, 2008.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Statement made by Philipp Haager in an email on May 19, 2010.

[4] Frank-Thorsten Moll, 2008.

[5] Statement made by Philipp Haager in an email on May 19, 2010.

[6] Michael Jacob, “Im Himmel lesen oder warum Wolken bedeuten,” in: Stephan Kunz, Johannes Stückelberger, Beat Wismer (eds.), Wolkenbilder, Die Erfindung des Himmels, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Hirmer Verlag, Munich, 2005, pp. 71–73, here: p. 71.

[7] Cf. Acts of the Apostles 1, 9–11: “And when he had said these things, while they looked on, he was raised up: and a cloud received him out of their sight. [...] This Jesus who is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come, as you have seen him going into heaven,” quoted in: Rainer Guldin, “Windschiffe. Die Wolke als Fahrzeug und Bühnenrequisit,” in: Stephan Kunz, Johannes Stückelberger, Beat Wismer (eds.), Wolkenbilder, Die Erfindung des Himmels, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Hirmer Verlag, Munich, 2005, pp. 39–42, here: p. 40, (English version from the Latin Vulgate Bible).

[8] Cf.: Hartmut Böhme, “‘Was birgt die Wolke?’ – Zur Kultur- und Kunstgeschichte von Wolken und Wetter,” in: Stephan Kunz, Johannes Stückelberger, Beat Wismer (eds.), Wolkenbilder, Die Erfindung des Himmels, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Hirmer Verlag, Munich, 2005, pp. 11–21, here: p. 11.

[9] Hartmut Böhme, 2005, p. 12.

[10] Hartmut Böhme articulated this development as follows: “In artworks, clouds were only able to unfold their own pictorial aesthetic once paintings were freed from their golden backgrounds, allowing perspectives into space and horizons to open up, when room was gradually made for landscapes and the sky took on its own aesthetic quality.” Cf.: Hartmut Böhme, 2005, p. 13.

[11] Hartmut Böhme, 2005, p. 14.

[12] Gernot Böhme, “Bild der Dämmerung,” in: Böhme, Architektur und Atmosphäre, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich, 2006, pp. 54–73, here: p. 67.

[13] Ibid., p. 70.

[14] Ibid., p. 70.